Arguments in order of publication.

Complexity, ecosystem . . .

Expanding forests . . .

Forest greening - forest browning . . .

Biodiversity - why is this word so complicated?

Hardwoods or softwoods to store carbon

Scots-pine: the worlds most successful tree?

Pine wood regeneration: natural or by planting?

Complexity, ecosystem and the art of the soluble

A pond, a meadow and a forest, in Poland. Photo credit Wikipedia

This photograph illustrates parts of a landscape that are often called ecosystems. A scientific definition of an ecosystem is more difficult. Boundaries of the forest are vague. How many species of the forest are included - all the trees, but what about all smaller plants and microbial life of the soil? System implies functional interconnections between most or all parts of the system but in the vast assemblage of species within a forest how can this be possible? An alternative perspective for understanding of how a lake or meadow or forest works as a whole is to study its parts, as those species that are accessible to be counted, measured and weighed. How those species might interact with others close by is best understood by studying how they have evolved by natural selection to survive and reproduce well within the forest.

For the full argument download here:

Are the world's forests really expanding?

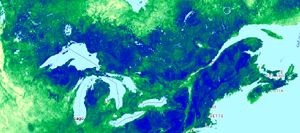

Forest cover in part of North America mapped using satellite data; yellow to blue = least to most.

News reports of deforestation and forest fires in the context of the climate crisis are often depressing. But is this the whole story or is there more happening to forests that is cause for optimism? Yes is the short answer, but as often with ecology the story contains accounts of reliable research that seem contradictory. This argument presents the case for optimism when these studies are balanced against each other.

For the full Argument download here:

Forest greening - forest browning

Beech leaves in spring

This Argument is related to the question of whether or not the forests of the World are expanding as measured by their area, in square kilometres or reforestation of formerly deforested regions. These contrasting descriptions of the overall appearance of vegetated and forested land refer more the health of the vegetation: green good but brown more likely to indicate less good health, or lower productivity. This type of information on the state of forests can be assessed on the ground by foresters but huge areas of land can be surveyed by satellites configured to provide several indices of vegetation health and productivity.

The question here is about the balance between trends of increased greening against trends of increased browning. The data available show the balances tilting either way depending on region and how the data were gathered.

For the full Argument download here:-

Biodiversity - why is this word so complicated?

A diversity of two species of fly seeking nectar from the flowers of angelica plant.

Biodiversity is a term invented a few decades ago as a technical alternative to plain nature. Biodiversity is used in many ways, an example is a style of presenting information about how the world works in terms of a group of 9 environmental categories. These are represented as segments around the central globe of Earth. A conspicuous segment is that for biodiversity. It reaches far from the core of safe limits for humanity, measured as extinctions of species. Next is a smaller segment for land-use. These two categories have different metrics, not directly comparable. However, loss of biodiversity is caused by the land-uses of agriculture and plantation forestry. This incompatibility obscures an opportunity for practical action. Which is to to define a safe balance between land area for nature and land area for food and timber crops. Then regenerate land for nature along with making agriculture more efficient.

For the full Argument download here:-

Hardwoods or softwoods to store carbon?

Harvest from a plantation of pine and beech trees: softwood and hardwood.

Climate heating resulting from increase in concentration of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere can be reduced by planting more trees. These will take up the carbon dioxide during photosynthesis and convert much of that into the carbon content of the wood of stems, branches, roots and other tissues. Which trees might be best for this? Do hardwood trees contain more carbon than softwood trees and is that what makes their wood hard? Does a forest or a plantation of softwood trees contain more carbon per hectare of land on which they stand than would hardwood trees on the same land? There are answers to these questions which might seem counter-intuitive, and the questions need to be relevant to the purpose of the woodland or forest. This Argument provides some straightforward answers but also asks questions about the wider context of how forests and plantations are managed.4

Full the full Argument download here:-

Scots-pine: the world's most successful tree?

Distribution of Scots pine, Pinus sylvestris, from Atlantic Ocean to Pacific Ocean.

The argument made here is that a species of tree that has established itself over such a wide area of suitable habitat on Earth, and that is also well regarded as both a timber tree to grow in plantations, and a highly attractive tree to people when it is growing naturally has special character. That is: a character of success as an experiment in the process of evolution.

For the full Argument, in format of a slide-show, download here

Pine wood regeneration: natural only or with planting?

Scots pine wood showing natural regeneration in the foreground.

Scots pines growing in Scotland within their native region are as scattered woods, now greatly reduced from their original density. This deforestation resulted from over-exploitation. Now that this has ceased there is opportunity to regenerate these woods. Many groups of people are active for this, but how best to do it is controversial. To rely exclusively on natural regeneration by seed from existing woods, or to make much additional use of planting seedlings? Natural regeneration will retain the valuable high level of genetic diversity of the national population of these pines but it will be slow. Planting will be faster but with lesser genetic diversity of the stock. Which might prove best in the long term?

Download Pinewood regeneration.